FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Babesiosis (Babesia microti)

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)

DISCUSSION

Babesiosis:

Babesiosis is an infection caused by the parasite Babesia microti (mostly, some other species exist). In the United States, B. microti has been identified in the Northeast and upper Midwest states, while B. duncani has been identified on the West Coast (CA, WA). A new, unnamed strain has also been identified in Missouri (MO-1). In Europe, most cases are due to B. divergens, and occasionally B. venatorum.

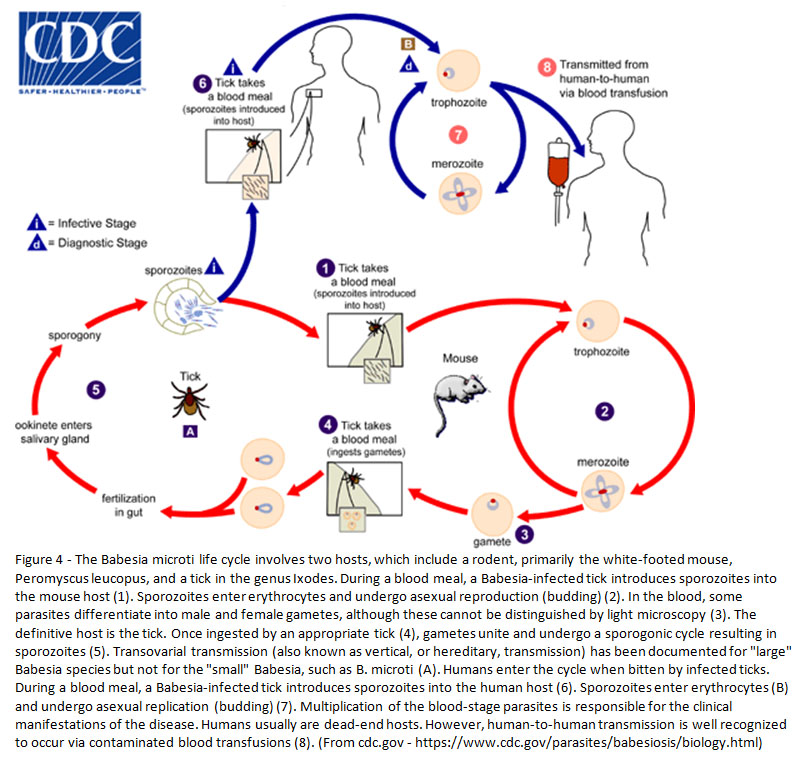

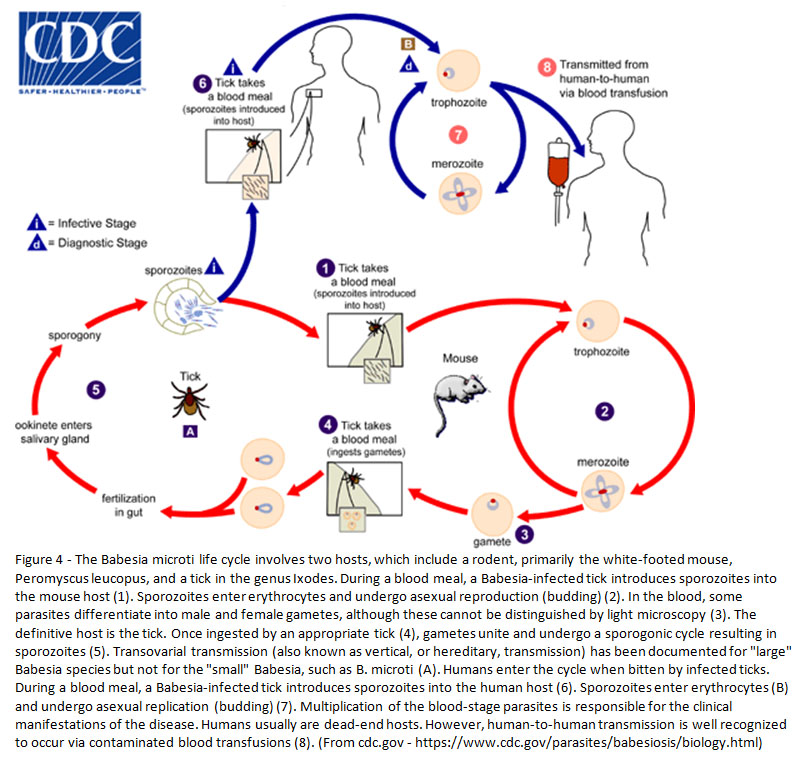

Vector and lifecycle (1, 2):

The definitive hosts of Babesia spp. are Ixodes spp. ticks (particularly I. scapularis). Additional stages of the lifecycle occur in rodents, particularly the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus). Humans are an incidental, terminal host. See Figure 4 for a complete description of the lifecycle. Importantly, Ixodes scapularis is also a vector for Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (anaplasmosis) and Powasson virus.

Transmission (1,2):

The primary method of transmission is by Ixodes spp. tick bites, which introduce the organisms (sporozoites) into the blood stream. The organisms infect red blood cells, where they are able to multiply. Infection most commonly occurs during the spring and summer (warm months) when tick nymphs are feeding.

Additionally, organisms can be transmitted by blood transfusion from an infected donor. This is uncommon due to donor screening questions (indefinite deferral), though there is not a mandated laboratory screening. One study examined arrayed fluorescence immunoassay (AFIA) and PCR screening of donated blood, with 0.38% and 0.075% of samples testing positive, respectively (3).

There are also rare case reports of transplacental transmission.

Clinical presentation (1, 2):

Many infections are likely asymptomatic. Clinical symptoms typically develop within 1-4 weeks, but can take months, and the infection may remain latent until a period of immunosuppression. These symptoms often include fever, chills, myalgias, weakness and fatigue. Patients may also experience hemolytic anemia, hepatosplenomegaly or jaundice. In severe cases, patients may present with thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hypotension, respiratory failure, myocardial infarction, acute renal or liver failure, or altered mental status. Severe infections can be fatal.

Diagnosis (1, 2):

The primary method of diagnosis is identification on a blood smear by light microscopy (thick and thin smears). The trophozoites appear as variably sized rings which may be round, oval or pear-shaped with pale blue cytoplasm. Extracellular rings may be identified. Occasional tetrad forms may be seen ("Maltese cross").

Additionally, antibody testing (indirect fluorescent, IFA) or molecular testing (i.e. PCR) can be utilized for diagnosis.

Treatment (1):

Treatment consists of at least 7-10 days of either:

Clindamycin and quinine are typically used in severe infections. Exchange transfusion may be indicated for B. divergens infections. Additional treatment for other symptoms (supportive care) may also be required.

Comparison with malaria (1, 2, 4):

The morphology of Babesia spp. can sometimes be confused with malaria (particularly P. falciparum), as they are both small parasites that infect red blood cells. Both organisms are seen as ring forms within red blood cells, and both can have multiple rings within a red blood cell. However, Babesia spp. lack pigmentation (hemozoin) as well as gametocyte, trophozoite and schizont forms in human infection. Additionally, Babesia spp. can be seen outside of the red blood cells (extracellular rings), and may also form tetrads.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH):

HLH is a disorder of excessive inflammation which results in tissue destruction. This involves activation of macrophages, cytotoxic T-cells and NK-cells, as well as the production of excess cytokines (5).

Clinical presentation (5):

The clinical presentation often includes fever and hepatosplenomegaly, and may also include lymphadenopathy, rash and neurological symptoms. Additionally, some patients may develop respiratory failure, hypotension, acute renal failure or bleeding. Some primary forms may also have symptoms associated with the underlying genetic syndrome.

Primary vs. secondary:

Primary HLH (familial HLH) is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in either FLH gene loci or several immunodeficiency-related genes. Secondary HLH does not have germline mutations and is the result of any number of triggers, including infection, malignancy, autoimmune disorders, and others. In relation to the current case, babesiosis (rarely) and CLL/SLL are reported to be triggers for HLH (5, 6).

Diagnostic criteria:

HLH-2004 Revised Diagnostic Guidelines (7):

Treatment (8):

Treatment may include rituximab, etoposide, cyclosporine, steroids, methotrexate, or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). For infection-associated cases, appropriate antimicrobial therapy is also indicated. Some patients may require hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

REFERENCES

![]() Contributed by John M. Skaugen, MD, Nidhi Aggarwal, MD, and Grant Bullock, MD, PhD

Contributed by John M. Skaugen, MD, Nidhi Aggarwal, MD, and Grant Bullock, MD, PhD